Why people with criminal histories struggle to find jobs in Oregon

written by Pam Ferrara for the Salem Reporter

August 29, 2023

Individuals with criminal histories have difficulty finding jobs, even with an unemployment rate at rock bottom. This is a problem for them, for the economy and for society as a whole.

The Willamette Workforce Partnership, the workforce board for Linn, Marion, Polk and Yamhill counties, will receive a portion of some four million dollars recently awarded to the state association of workforce boards to help those preparing to be released from prison find employment.

The reasons that those with criminal histories are unemployed at far higher rates than other job seekers are many and complex.

Let’s look at the size of the problem from several perspectives, some research on the demographics of prison populations, some “best practices” for helping the situation, and some final thoughts on this intractable problem.

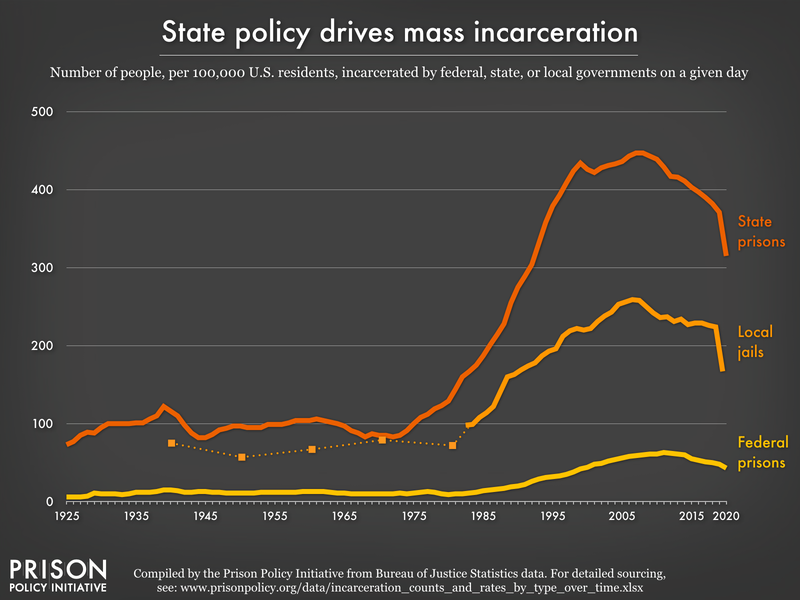

First, the numbers – some 22,000 people were imprisoned as of May 2023, in Oregon’s state prisons, federal prison, juvenile facilities, and local jails, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. This translates to Oregon (and 49 other states and the U.S.) having a higher incarceration rate per 100,000 population than most countries in the world.

These large numbers are fairly recent (see graph).

Prison populations began to soar in the 1970s with the war on drugs and policies such as mandatory minimum sentencing and three-strike laws.

Why are high rates of incarceration a problem?

Incarceration is costly. It is estimated that the 98 federal prisons and 1,566 state prisons in the U.S. cost eighty billion dollars annually to operate.

The Oregon Department of Corrections, in charge of Oregon’s 14 state prisons, has a biennial budget of two billion dollars, two percent of the state’s budget. The cost of running Oregon’s federal prison, juvenile facilities and county jails adds to this amount. For example, in 2017 the Marion County Jail was reported to cost twenty million dollars annually. It underwent an expansion to add beds and personnel in 2022, costing another two million.

In addition, it’s estimated that indirect costs of incarceration such as lost earnings and the economic and social damage to prisoners’ families are many times the direct costs. For the U.S. as a whole these could total a half a trillion dollars annually. How high are unemployment rates for those with criminal histories? The official source of unemployment rates, the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), does not publish rates for these individuals. But BLS used one of their own longitudinal surveys to estimate that, in the early 2000s, one-third of young men had a job in the first few weeks after release from prison, and by 12 weeks, about half had jobs. Out to week 78, between 50 and 58 percent had jobs.

Other studies arrive at slightly different but in-the-ball-park numbers. One such study concluded that as many as 60 percent of those with criminal histories are unemployed four years after release from prison.

Why is it so difficult for those with criminal histories to find and keep jobs?

The short answer is: employers don’t want to hire them. That is the assumption of the “ban the box” initiative. Oregon passed such legislation several years ago to make it unlawful for employers to ask about criminal history before the interview stage of hiring – in other words, banning asking about criminal history on the initial job application. The additional assumption is that, once an individual with a criminal history has a chance to be interviewed, he/she will have a better chance of being able to demonstrate skills, etc., and possibly land a job.

There’s a more complicated answer, and it lies in the demographics of those who become incarcerated. The majority of individuals who are incarcerated bring with them a myriad of troubles. When they are released, often the challenges of their past accompany them.

What are these problems? Finding statistics isn’t easy. Many researchers comment on the lack of good and current information. The two main sources of information about our population, the Current Population Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, don’t ask about criminal histories.

The U.S. Department of Justice does a periodic survey of prison populations, and the latest was in 2016 (see table below).

Federal Dept. of Justice Survey of Federal and State Prisoners 2016* |

|

| Male | 93% |

| Age at time of interview | |

| 18-24 | 10% |

| 25-34 | 32% |

| 35-44 | 27% |

| 45-54 | 19% |

| 55 or older | 13% |

| Homeless in the year before offense | 14% |

| Had a serious psychological distress in the 30 days prior to offense | 13% |

| Substance abuse at time of offense | |

| Alcohol | 30% |

| Any drug | 38% |

| Parents or guardian received public assistance, for those aged 18-24 | 42% |

| Education less than high school | 62% |

| Parent of a minor child | |

| Aged 18-24 | 41% |

| Aged 25-44 | 64% |

| Ever lived in foster home, institution | 15% |

| African-American | 34% |

| Hispanic | 23% |

| Native American | 2% |

| Married | 15% |

| Widowed, Separated, Divorced | 27% |

| Never Married | 58% |

| Number of Prior Incarcerations | |

| 0 | 22% |

| 1 | 18% |

| 2-4 | 30% |

| 5-9 | 19% |

| 10 or more | 12% |

| *From a national cross-sectional survey |

|

From this survey it can be concluded that a typical prison inmate was male, between the ages of 18 and 44, somewhat likely to be a minority, lacked a high school diploma, had never been married, had minor children, came from a home where parent or guardian received public assistance, and had prior incarcerations.

The Oregon Department of Corrections provides some current information on approximately 12,000 individuals in state prisons. In addition to basic demographics, Corrections provides the results of assessments for mental health needs and substance abuse.

As of August 2023, 31 percent of inmates were in the “highest treatment need” or “severe mental health problems” for mental health services. Another 31 percent had moderate mental health needs or could benefit from mental health treatment. Sixty-six percent of inmates had “some substance abuse” or “dependence/addiction.”

Most prisons don’t have programs to treat these problems. A bill in the last Oregon legislature would have mandated expanded access to behavioral health care in state prisons, but didn’t pass the session.

Let’s circle back to helping those with criminal histories find employment. There are many programs that do this, and they are called re-entry programs. The de Muniz Center of the Mid-Willamette Valley Community Action Agency is a local one. Their website emphasizes helping individuals stabilize their lives, a recognition of the many problems other than criminal history that individuals cope with upon release from prison.

Research on the evidence of the effectiveness of re-entry programs deems them modestly effective. One study that reviewed and analyzed a number of re-entry program databases concluded that “…interventions can improve some employment outcomes for people released from prison.”

The Prison Policy Initiative , with 22 years of experience researching and advocating for reforms, concludes that the U.S. warehouses “…. those struggling with poverty, substance use disorders, and housing insecurity, among other serious problems.” Public policy responses to social inequities in the U.S. are to blame for the size of the incarcerated population.

The funds that will be expended by the local workforce board and other boards around the state will help some. According to the Oregon Department of Corrections, 423 individuals were released from state prisons into Marion County in 2022. And, nearly half the state prison population is within two years of release.

But helping those with criminal histories find employment is only a small part of the solution.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected]