Employers will likely struggle to fill high-demand jobs in the Salem area

written by Pam Ferrara for the Salem Reporter

November 8, 2022

“We’ve just been through the greatest disruption to the workforce since World War II.”

So say the researchers of ECONorthwest, a Portland consulting firm, in a report prepared for the state workforce board last spring.

Has the workforce recovered from “the great disruption?” What challenges do job-seekers, the local workforce board (working in the mid-Valley counties of Marion, Polk, Linn and Yamhill) and its job-training programs, and the mid-Valley’s 21,000 employers face in late fall of 2022?

Job loss early on in the pandemic was record-breaking as mid-Valley counties lost 31,000 jobs in one fell swoop from March to April of 2020.

As of September 2022, total employment in the mid-Valley is almost completely recovered – it’s less than one-third of one percent lower than before the pandemic. The exception is the Leisure and Hospitality industry, especially hotels, motels, and restaurants. The industry is still 12 percent below its pre-pandemic employment level, and ECONorthwest, in its report, predicts that industry employment won’t completely recover until 2026.

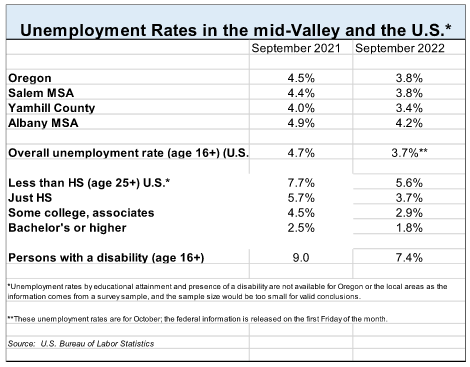

Current historically low unemployment rates are another sign of labor market recovery.

But demographic differences in the rates still hold up. (see table below)

Those job seekers with lower levels of education have higher unemployment rates, as well as those aged 16-19, and those with a disability. However, even these rates are at historic lows.

Low unemployment rates make hiring difficult for employers. And, according to the ECONorthwest report, because of the pandemic, “workers for a variety of reasons have become more selective about the work they do.”

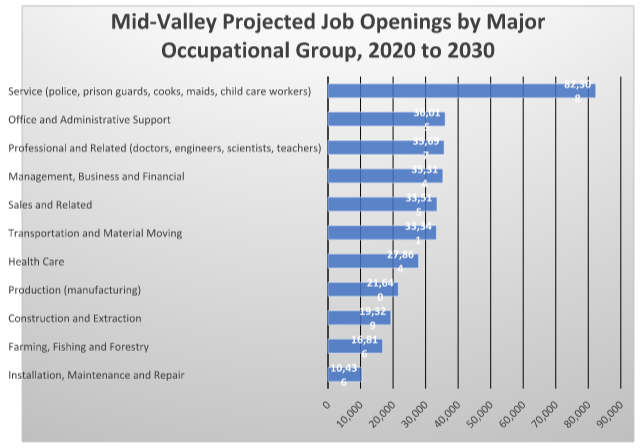

Nevertheless, employers will be hiring for approximately 350,000 openings in the four counties over ten years, according to the Oregon Employment Department’s occupational projections for 2020 to 2030. (see graph below)

Future Ready Oregon, the state’s $200 million job training program, has targeted three occupational groupings as priorities. These are health care, manufacturing (production occupations) and technology (computer occupations).

What do the projections say about these occupational groupings over the next ten years?

More than half of the mid-Valley’s 25,000 job openings in health care occupations will be for home health aides, medical assistants and nursing assistants, all with pay in the lower ranges. There will be openings for 2,700 nurses, but hiring a nurse, even though it is a well-paid occupation, will be a challenge. According to ECONorthwest, in a recent school year, all state institutions awarded only 1,600 nursing degrees. There could be a dire shortage of nurses.

Of the mid-Valley’s 18,000 production openings, nearly one in five pay $20 an hour or less. Production occupations that pay well require certifications which don’t appear to be coming through the pipeline in sufficient numbers to meet demand, according to ECONorthwest. Employers will continue to find it difficult to fill openings for machinists and CNC machine operators, for example.

And lastly, applying for computer-related openings may be challenging for job-seekers who want to stay in the mid-Valley. There will be some 3,000 openings in nine occupations, all of which pay more than $30 an hour. However, it appears that far more credentials are being awarded relating to these occupations than projected numbers of openings, according to ECONorthwest. There may be an over-supply of job seekers for computer-related jobs.

Where will the workers come from?

This brings us to the concept of labor force participation, which is a measure of labor supply. It is defined as those working and those looking for work, divided by the civilian population aged 16 and older, and expressed as a percentage.

Labor force participation declined in Oregon (and everywhere else) during the pandemic, but it’s now at a ten-year high. However, over the long term, it has been declining. (see graph, next page)

Men’s participation, especially for those with educational attainment of less than high school, has been declining for decades. This is not unique to the U.S. as it is related to a shift from a goods-producing to a service industry economy in western industrialized countries.

Women’s participation has been declining since 2000. This decline is unique to the U.S. and is related to less-than-family-friendly labor policies.

What does all this mean?

Firstly, everyone (almost everyone) who wants a job has one. There is no doubt that this labor market is a boon to those who’ve had a difficult time becoming employed in the past.

The labor market situation is a challenge to the Willamette Workforce Partnership and its job training contractors. Providing training in the midst of low unemployment rates means that those who need training have multiple barriers to becoming employed. Removing these barriers to get these folks job-ready wont’ be easy. Another challenge will be finding those not participating in the labor force – how will WWP reach out to these potential workers?

Employers will face challenges in hiring for job openings. They may continue to raise wages. Putting more family-friendly workplace policies into place would help. And lastly, they may possibly look for ways to support immigration reform as most economists say that the current U.S. immigration policies are restricting labor supply – the last reform was in 1986.

Last but not least, what about inflation, and will there be a recession? Overall inflation has slowed some over the last few months, although food, energy and transportation-related items have had double-digit percentage increases over the year. The Federal Reserve Board continues to raise interest rates. According to the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, if recession happens, and there doesn’t appear to be a consensus that recession is a certainty, it will arrive later in 2023.

The bottom line, then, is that the economy is a good one for workers, especially those who’ve had trouble becoming employed in the past, and those workers in occupations in the lower pay ranges, who are seeing rising wages.

Employers will continue to struggle to fill openings, and the workforce board will need to be creative about finding potential job applicants and getting them ready for employment. All this could change if a recession begins to look likely. Only time will tell.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected]