Lower wages, higher barriers to entry among reasons fewer Oregon teens work

written by Pam Ferrara for the Salem Reporter

March 8, 2022

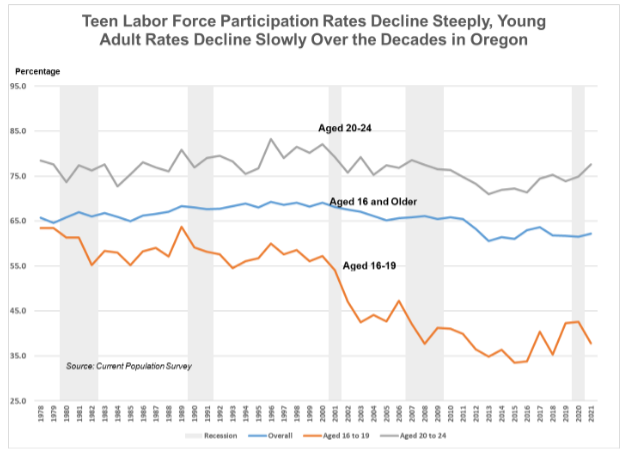

Are youth endangered in the labor force? Labor force participation rates (the percentage of the civilian non-institutionalized population working and looking for work) for young people between the ages of 16 and 24 have declined substantially and their unemployment rates have increased over the last few decades.

The labor force participation rate is an important measure of labor supply, and declining youth participation is a problem for employers and the economy. When young people look for a job and can’t acquire one, it’s a problem for them and possibly for their acquiring a stable financial future.

Young people’s participation in the labor force has declined, and their unemployment rates have risen because the world of work is more difficult to navigate for teens and young adults than it was years ago.

This is due in large part to the restructuring of the economy and its economic and societal consequences for the Salem area, Oregon, and the U.S.

Wages for jobs requiring minimal skills – jobs most young workers start out doing – have fallen dramatically over the last five decades or so. Consequently, there is a larger than-ever wage premium for jobs that require skills and education. Employer-sponsored training was more common in earlier decades than now, and education has become expensive and out of reach financially for many.

Additionally, research shows many societal barriers hinder youth from getting a good start in the labor market. The effects of these often persist into adulthood and negatively influence individual, family, and community well-being. These barriers include living in poverty, being a teen mom or dad, a high school dropout, a youth aging out of foster care, being disconnected from both school and work, and being involved with the juvenile justice system.

Let’s look at youth labor force participation and youth unemployment over the decades to see how these have been affected.

For the purpose of economic research, “youth” is generally divided into two age categories, aged 16-19, and 20-24. The reason for the division goes something like this: Teens aged 16-19 are likely transitioning out of high school into work, post-secondary training or education, or into college. Some work part-time while in high school or in the summer – more on this later. Youth aged 20-24 are transitioning as well, likely out of college into their first “real” job.

Teen labor force participation has dropped precipitously over the last few decades.

It recovered some in the years before the pandemic, due to the extremely tight labor market and historically low unemployment rates.

Two extensive surveys from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (1979 and 1997 Longitudinal Survey of Youth) tell us that much of the decline is because far fewer teens work during high school, or in summer jobs, than previously. This is significant because the survey also found that working during high school or in the summer was correlated with being successful at work later on. (Surveyors interview 15- and 16-year-olds and follow up with them for 20 years).

It is widely assumed that a major reason for less work during high school is that the increase in workplace safety regulations has resulted in fewer jobs suitable for teens. However, survey results presented a more complicated picture.

One significant survey finding was that youth living in single-parent households were far less likely to work during school or summers than those in two-parent households. Possible reasons cited were: two-parent families were more likely to be affluent, and able to provide teens with access to a car; higher-income two-parent families were more likely to have workplace connections to benefit their teens; and youth in single-parent families were more likely to be needed to help with housework and child-care.

Single-parent families have become a much larger portion of all families over the decades, and approximately one-third of single-parent families live at or below the poverty line. In Marion County, 32 percent of children under age 18 lived in single-parent families in 2019. The median income for Marion County single mom families was $29,545; single dad families $43,185, and married couple families $81,181.

Older youth, the 20- to 24-year-olds, have experienced declining labor force participation as well, although not as drastically as teens. Participation peaked in 1996 at 83 percent, then declined slowly to 71 percent in 2013 – not surprising as the recovery after the 2008 recession was slow. Participation is slightly on the upswing again as the economy recovers from the pandemic. Some research suggests that increasing college attendance accounts for much of the decline.

And it now takes longer to finish a four-year college degree (six years is now the norm) than it used to.

When a person is unemployed, he/she participates in the labor force by looking for a job. The teen unemployment rate has generally been two to three times the rate of those 25 and older and the unemployment rate for youth aged 20 to 24, is nearly twice that rate.

Tight labor markets such as we are experiencing now, and just before the pandemic, have benefitted youth employment. However, the overall trend is still higher than normal unemployment for both categories of young people. And, it didn’t start out that way – it has gradually worsened as the U.S. economy has changed, as described earlier in this column.

Workforce public policy in the U.S. recognizes the special problems of youth in the labor market. Part of the federal funding received by the 600 or so workforce boards across the U.S. is designated for programs to help youth get ready for a job. The Salem area workforce board, the Willamette Workforce Partnership is currently helping 61 youth in Marion County get job-ready. Other organizations help as well but the need is great.

The Marion County Board of Commissioners recognized the need by providing funding to subsidize wages for small businesses to employ 14- to 17-year-olds in their first job. The state of Oregon may provide funds to continue this now-completed program and additional funds for the workforce board’s youth program. These are good ideas and steps in the right direction.

Pam Ferrara of the Willamette Workforce Partnership continues a regular column examining local economic issues. She may be contacted at [email protected]